Digest of my PhD thesis

Below is a short digest of my PhD thesis. The full thesis is available for download here.

Abstract

Timely and effective incident response is key to managing the growing frequency of cyberattacks. However, identifying the right response actions for complex systems is a major technical challenge. Framing incident response as an automatic (optimal) control problem is a promising approach to address this challenge but introduces new challenges. Chief among them is bridging the gap between theoretical optimality and operational performance. Current response systems with theoretical guarantees have only been validated analytically or in simulation, leaving their practical utility unproven.

This thesis tackles the aforementioned challenges by developing a practical framework for optimal incident response. It encompasses two systems. First, it includes an emulation system that replicates key components of the target system. We use this system to gather measurements and logs, based on which we identify a game-theoretic model. Second, it includes a simulation system where game-theoretic response strategies are optimized through stochastic approximation to meet a given security objective. These strategies are then evaluated and refined in the emulation system to close the gap between theoretical and operational performance. We prove structural properties of optimal response strategies and derive efficient algorithms for computing them. This enables us to demonstrate optimal incident response against real network intrusions on an IT infrastructure.

Introduction

Incident response refers to the coordinated actions taken to contain, mitigate, and recover from cyberattacks. Today, incident response is largely a manual process carried out by security operators. While this approach can be effective, it is often slow, labor-intensive, and requires significant skills. For example, a recent study reports that organizations take an average of 73 days to respond and recover from an incident. Reducing this delay requires better decision-support tools to assist operators during incident handling. Currently, the standard approach to assisting operators relies on response playbooks, which comprise predefined rules for handling specific incidents. However, playbooks still rely on security experts for configuration and are therefore difficult to keep aligned with evolving threats and system architectures.

A promising solution to this limitation is to frame incident response as an optimal control problem, which enables the automatic computation of optimal responses based on system measurements. Such framing facilitates a rigorous treatment of incident response where trade-offs between different security objectives can be studied through mathematical models. Prior research demonstrates the advantages of this approach in analytical and simulated settings. However, its feasibility for operational use has yet to be proven.

Addressing this limitation is the purpose of this thesis. We do so from three directions: via mathematical modeling, via experimental evaluation, and via systems engineering. Our main contribution is a practical framework for optimal incident response in IT systems. This framework is grounded in engineering principles for self-adaptive systems and has a rich mathematical foundation, which we systematically develop throughout the thesis. It draws on the theories of stochastic approximation, control, causality, and games. We prove theoretically and experimentally that our framework is superior to present solutions on several instances of the incident response problem, including responses against intrusions in enterprise networks, Byzantine failures in distributed systems, and advanced persistent threats in cloud infrastructures. Our key experimental finding is that the most important factor for scalable and optimal incident response is to exploit structure, both structure in theoretical models (e.g., optimal substructure) and structure of the IT system (e.g., network topology). The former enables efficient computation of optimal responses and the latter is key to managing the complexity of IT systems.

In summary, this thesis makes the following contributions:

1. Scalable algorithms for optimal incident response.

We design and implement seven scalable algorithms for computing optimal response strategies, for which we prove convergence. They build on techniques from stochastic approximation, game theory, reinforcement learning, linear and dynamic programming, and causality. We demonstrate that these algorithms outperform state-of-the-art methods in the scenarios we study.

2. Mathematical formulations of incident response.

We introduce six novel mathematical models of incident response. With these models, we show that a) optimal stopping is a suitable framework for deriving the optimal times to take response actions; b) partially observed stochastic games effectively model the incident response use case; and c) the Berk-Nash equilibrium allows capturing model misspecification in security games.

3. Proving structural properties of response strategies. We develop mathematical tools for incident response and prove structural properties of optimal response strategies, such as decomposability and threshold structure. These results enable scalable computation and efficient implementation of optimal strategies in operational systems.

4. General framework for optimal incident response.

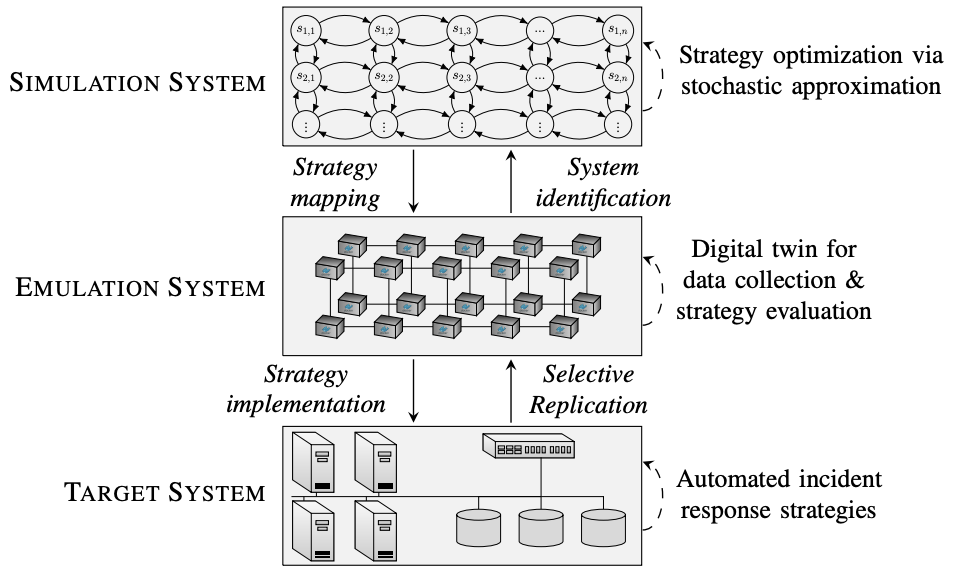

We design a general framework for optimal incident response; see Fig. 1. Additionally, we present the Cyber Security Learning Environment (CSLE), an open-source platform that implements our framework. Unlike previous simulation-based solutions, our framework provides practical insights beyond a specific response scenario. The source-code is available here.

Fig. 1: Architectural overview of our framework for automated, optimal, and adaptive incident response in IT systems.

The Incident Response Problem

Incident response involves selecting a sequence of actions that restores a networked system to a secure and operational state after a cyberattack. When selecting these actions, a key challenge is that the information about the attack is often limited to partial indicators of compromise, such as logs and alerts. Examples of response actions include network flow control, patching vulnerabilities, and updating access controls.

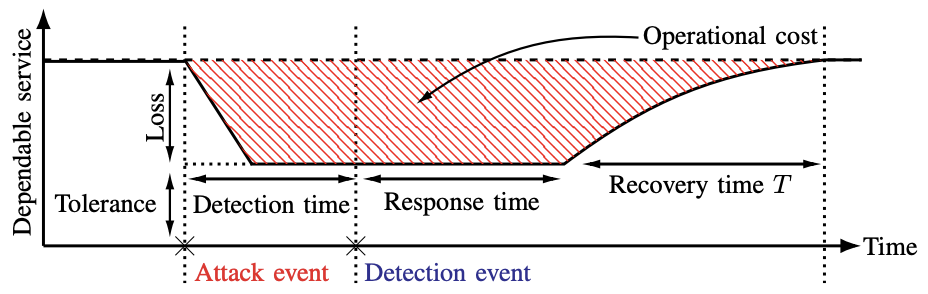

Figure 2 illustrates the phases of incident response. Following the attack are detection and response time intervals, which represent the time to detect the attack and form a response, respectively. These phases are followed by a recovery time interval T, during which response actions are deployed. The objective is to keep this interval as short as possible to limit the cost of the incident. For example, in the event of a ransomware attack, a delay of a few minutes in containing the attack may allow the malware to encrypt systems or spread laterally.

Fig. 2: Phases and performance metrics of the incident response problem.

Formalizing the Incident Response Problem

Before presenting our framework, we start by formulating incident response as a game-theoretic problem. To accomplish this formulation, we need a vocabulary in which to talk about the systems and actors involved. To this end, we refer to the operator of the target system as the defender, and we refer to an entity aiming to attack the system as the attacker. Both interact with the system by taking *actions (e.g., attacks and responses), which affect the system’s state (e.g., the system’s security and service status). When selecting these actions, the defender and the attacker use measurements from the system (e.g., log files and security alerts), which we refer to as observations. A function that maps a sequence of observations to an action is called a strategy, and a strategy that is most advantageous according to some objective is optimal.

Mathematically, the response problem can be stated as

\[\sup_{\pi_{D} \in \Pi_{D}}\inf_{\pi_{A} \in \Pi_{A}} \text{ } \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{D}, \pi_{A}}[J(\pi_{D}, \pi_{A}) \mid \mathbf{b}_1], \\ \text{subject to }\text{ } s_1 \sim \mathbf{b}_1, \\ s_{t+1} \sim f(\cdot \mid s_{t}, a_t^{(D)}, a_t^{(A)}), \text{ } \forall t \geq 1,\\ o_t \sim z(\cdot \mid s_t), \text{ } \forall t \geq 2,\\ \mathbf{b}_{t+1} = B(\mathbf{b}_{t}, a_t^{(D)}, o_{t+1},\pi_{A}), \text{ } \forall t \geq 1, \\ a_t^{(D)} \sim \pi_{D}(\cdot \mid \mathbf{b}_t), \text{ } \forall t \geq 1, \\ a_t^{(A)} \sim \pi_{A}(\cdot \mid \mathbf{b}_t, s_t), \text{ } \forall t \geq 1,\]where \(s_t\) is the game state at time \(t\), which is hidden from the defender; \(o_t\) is the observation; \(a^{k}_t\) is the action of player \(k\); \(\pi_{k}\) is the strategy of player \(k\); \(\mathbf{b}_t\) is the defender’s belief state, i.e., a probability distribution over game states; \(B\) is a belief estimator; \(z\) is the observation function; \(f\) is the transition function; and \(J\) is an objective functional that the defender tries to maximize and the attacker tries to minimize.

A Framework for Optimal Incident Response

To solve or approximate a solution to the above problem in a practical IT system, we have developed a general framework for incident response, which is illustrated in Fig. 1. It is centered around an emulation system for creating a digital twin, i.e., a virtual replica of the target system. (With target system, we mean the system where the learned response strategies are intended to be deployed.) We use this twin to run attack scenarios and defender responses. Such runs produce system measurements and logs, from which we estimate infrastructure statistics. These statistics allow us to instantiate our game-theoretic model of the target system through system identification. We then leverage this model to learn response strategies through simulation, whose performance is assessed using the twin. This closed-loop process can be executed iteratively to provide progressively better strategies that are adapted to changing operational conditions.

Emulation system. As described above, the emulation system in our framework is used to create a digital twin of the target system. The concept of a digital twin emerged in the 1960s when NASA used virtual environments to evaluate failure scenarios for lunar landers. Since then, digital twin has emerged as a key technology in automation and has been adopted in several industries, including the manufacturing industry, the automotive industry, and the healthcare industry. In our framework, a digital twin is a virtual replica of an IT system that provides a controlled environment for virtual operations (e.g., cyberattacks and responses), the outcomes of which can be used to optimize incident response strategies for the target system. Such a twin enables us to systematically test response strategies under different conditions, including varying attacks, operational workloads, and network latencies.

Simulation system. The simulation system in our framework is used to run optimization algorithms for learning effective response strategies. While these algorithms could in principle be executed directly on the digital twin, this approach is not practical due to the long execution times required for carrying out actions and collecting observations in the digital twin. For instance, executing a cyberattack or a response action in a digital twin can take several minutes. In contrast, the simulation system abstracts these processes, allowing cyberattacks and response actions to be executed within milliseconds.

With a simulation, we mean an execution of a discrete-time dynamical system of the form

\[s_{t+1} \sim f(s_t, a^{(D)}_t, a_t^{(A)}),\]where \(s_t\) is the system state at time \(t\), \(a^{(D)}_t\) is the defender action, \(a^{(A)}_t\) is the attacker action, and \(s \sim f\) means that \(s\) is sampled from \(f\). Each simulation path \(s_1,s_2,...,s_t\) is associated with performance metrics and operational costs. Our goal is to identify the defender actions that control the simulation in an optimal manner according to a specified security objective, such as quickly mitigating potential network intrusions while maintaining operational services.

The framework described above is broadly applicable, extending beyond any specific response scenario, infrastructure configuration, optimization technique, or identification method. It can be instantiated with concepts from diverse fields, including control theory, game theory, causality, and optimization. These concepts are developed in-depth both theoretically and experimentally throughout the thesis.

Framework Implementation

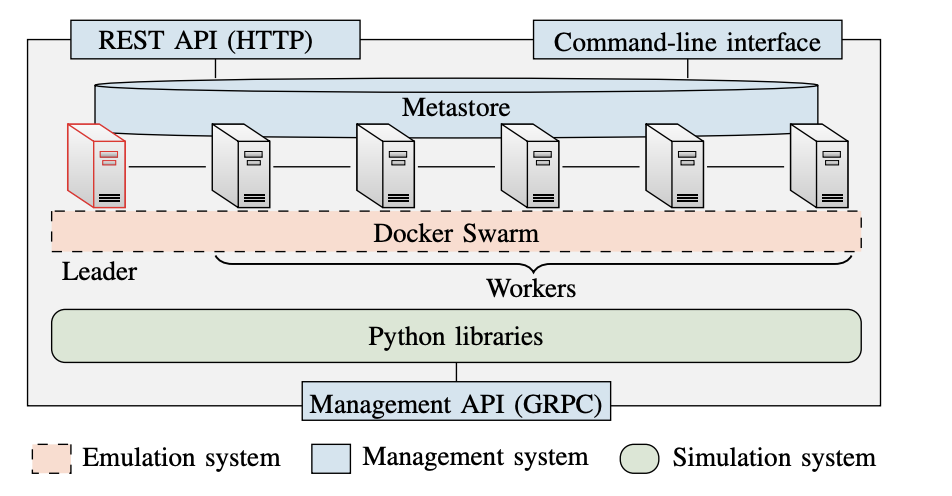

We have implemented our framework in an open-source software platform called the Cyber Security Learning Environment (CSLE). The source code of CSLE is released under the CC-BY-SA 4.0 license and is available in the repository here. The CSLE platform runs on a distributed system with N servers connected through an IP network and a virtualization layer provided by Docker; see Fig. 3. CSLE is implemented in Python (\(\approx 275,000\) lines of code), JavaScript (\(\approx 40,000\) lines of code), and Bash (\(\approx 5,000\) lines of code). It can be accessed through Python libraries, a web interface, a command-line interface, and a GRPC interface.

CSLE stores metadata in a distributed database referred to as the metastore, which is based on Citus. This database consists of N replicas, one per server. A quorum-based two-phase commit scheme is used to achieve consensus among replicas. One replica is a designated leader and is responsible for coordination. The others are workers. A new leader is elected by a quorum whenever the current leader fails or becomes unresponsive. CSLE thus tolerates up to \(\frac{N}{2}-1\) failing servers.

Fig. 3: The architecture of the software platform that implements our framework (CSLE). It is a distributed system with N servers (N=6 in this example), which are connected through a database (the metastore) and a virtualization layer provided by Docker Swarm.

The Emulation System

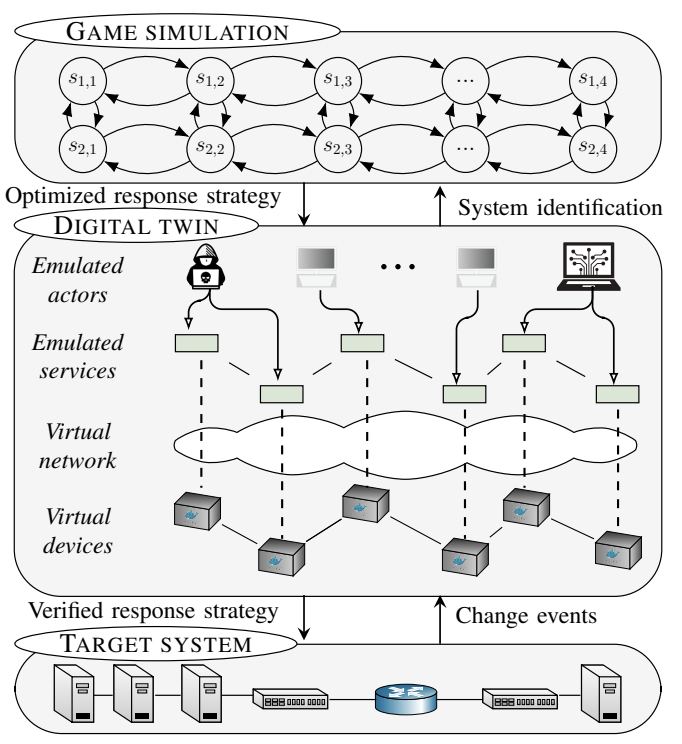

Creating a digital twin of a target system in our framework involves three main tasks: (i) replicating relevant parts of the physical infrastructure, such as processors, network interfaces, and network conditions; (ii) emulating actors, i.e., attackers, defenders, and clients; and (iii) instrumenting the digital twin with monitoring and management capabilities for autonomous operation; see Fig. 4. These three tasks are detailed below.

Emulating hosts and switches.

We emulate hosts and switches with Docker containers, i.e., lightweight executable packages that include runtime systems, code, libraries, and configurations. This virtualization lets us quickly instantiate large digital twins. Resource allocation to containers, e.g., CPU and memory, is enforced using Cgroups. Containers that emulate switches run OVS and connect to controllers through OpenFlow. Since the switches are programmed through flow tables, they can act as switches or as routers.

Emulating actors.

All actors in CSLE are programmatically controlled through a management API that allows changing configuration parameters, starting new actors, and stopping running ones. This automation enables attackers, clients, and defenders to operate in a fully autonomous environment.

We emulate clients of the target system through processes in the digital twin that access services on emulated hosts. For example, a client may be emulated by a process that consumes a web service of a Docker container for a period of time and then terminates. In a similar way, attackers in CSLE are emulated as autonomous processes that execute actions from a pre-defined library, including reconnaissance commands, privilege escalation attempts, brute-force logins, and exploits. The defender is modeled in a similar way, with response actions implemented as automated system commands.

Emulating network links.

We emulate network connectivity in digital twins through virtual links implemented by Linux bridges and network namespaces. Network conditions of virtual links are created using the NetEm module in the Linux kernel. This module allows setting bit rates, packet delays, packet loss probabilities, and jitter. For example, the standard configuration in CSLE is to emulate connections between servers in an IT system with full-duplex lossless connections of 1 Gbit/s capacity in both directions. Similarly, the default configuration for external communications is full-duplex connections of 100 Mbit/s capacity and 0.1% packet loss with random bursts of 1% packet loss. These numbers are based on measurements on wide-area networks.

Fig. 4: A digital twin in our framework is a virtual replica of a target system that runs the same software but on virtualized hardware.

The Management System

The role of the management system in CSLE is to support the operation of digital twins and facilitate reinforcement learning experiments and operation. In particular, the management system provides APIs for real-time monitoring and control of digital twins, as well as a web interface for managing reinforcement learning experiments and deployments.

Each emulated device in a digital twin runs a management agent, which exposes a GRPC API. This API is invoked to perform control actions, e.g., restarting services and updating configurations. To monitor processes and services running inside the digital twin, we use a monitoring system based on a publish-subscribe architecture. Following this architecture, each emulated device in a digital twin runs a monitoring agent, which reads local metrics of the host and pushes those metrics to an event bus implemented with Kafka. The data in this bus is consumed by data pipelines and control strategies.

The Simulation System

The simulation system in CSLE is implemented in Python and consists of reinforcement learning environments and algorithms for learning and identifying parameters of response strategies. All environments follow the OpenAI Gym interface, which allows integration with standard reinforcement learning frameworks. Each environment defines a Markov decision process or a game and can be configured through Python configuration files. CSLE includes an initial set of 34 reinforcement learning algorithms, over 50 simulation environments, and 4 identification algorithms, all of which can be extended.

Example Use Cases to Evaluate Our Framework

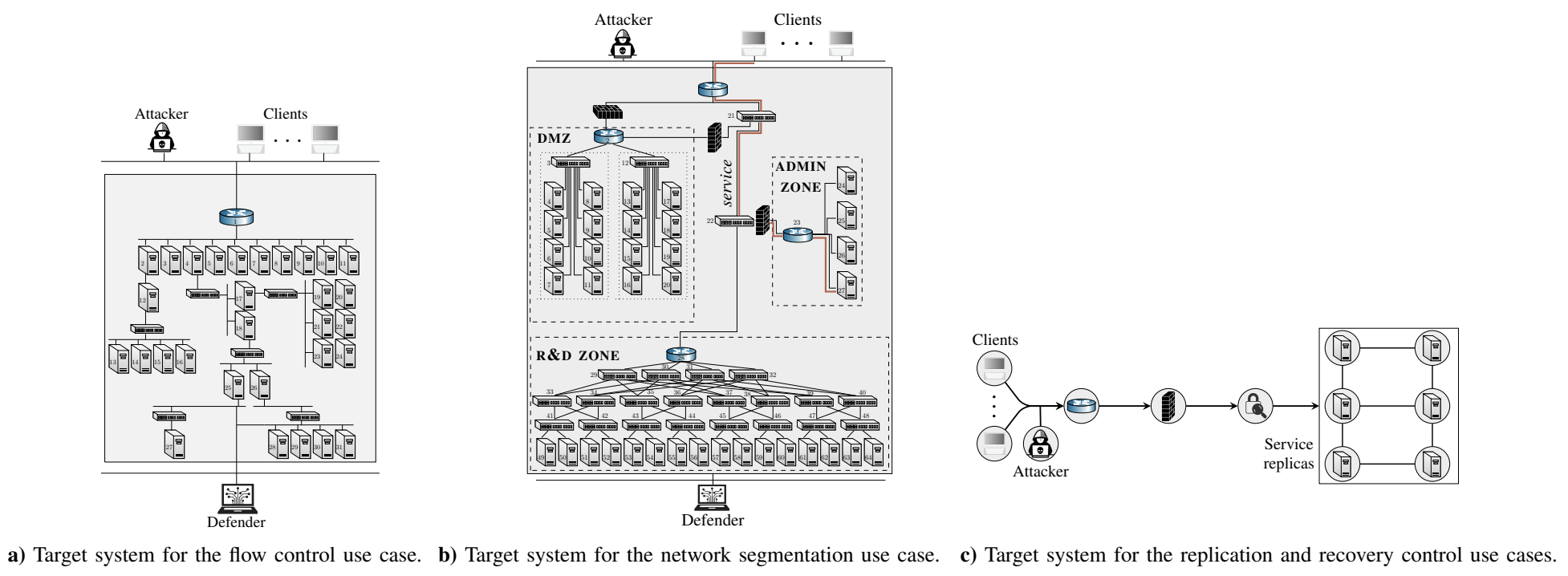

We demonstrate our framework by applying it to four different use cases: network flow control, network segmentation, replication control, and recovery control. Each use case involves a target system and a system operator (which we refer to as the defender) that can take response actions; see Fig. 5. The example use cases are described in detail below.

Fig. 5: Target systems for the use cases in the evaluation. The detailed system configurations are available in the thesis.

Flow control.

This use case involves an IT system that provides services to clients through a public gateway; see Fig. 5.a. Though intended for service delivery, this gateway is also accessible to an attacker who aims to intrude on the system. The defender monitors network traffic by accessing and analyzing alerts from an intrusion detection system (IDS). It can control network flows to mitigate possible intrusions. For example, it can block suspicious network flows or redirect them to a honeypot. In deciding which response actions to take, the defender has two objectives: maintain service to its clients and keep a possible attacker out of the system.

We formulate two different control problems based on this use case. First, we consider the problem of deciding when to block network flows at the gateway based on the IDS alerts. In this problem, we assume that the attacker follows a fixed strategy, which means that we can model the task as a partially observed Markov decision process (POMDP) where the observations correspond to IDS alerts, the states represent the security statuses of the system, and the actions correspond to flow controls. Second, we consider the problem of learning a flow control strategy that is effective against a dynamic attacker that adapts its strategy to circumvent the defenses. We model this problem as a partially observed Markov game, which resembles the POMDP but differs by also modeling the actions of the attacker. For mathematical details about the POMDP and the game, see the full thesis.

Replication control. This use case involves a replicated system that provides a service to a client population; see Fig. 5.c. The replication enables the system to withstand failures, provided that failed replicas are recovered faster than new failures occur. The defender monitors the failure statuses of replicas through failure alerts and responds by controlling the replication factor.

We formulate two different control problems based on this use case. First, we consider the problem of controlling the replication factor under a fixed failure distribution. We model this problem as a POMDP where the actions represent replication controls. Second, we consider the problem of learning a replication strategy that is optimal against an attacker that adapts its strategy based on the replication. We model this problem as a partially observed Markov game where the attacker’s actions correspond to exploits and the defender’s actions correspond to replication controls. For mathematical details about these models, see the full thesis.

Recovery control. This use case is based on the same target system as in the preceding replication use case. However, here we consider the problem of deciding when to initiate recovery of the service replicas. We formulate this problem as a POMDP where the actions represent recovery controls. For mathematical details about the POMDP, see the full thesis.

Network segmentation. This use case involves a cloud infrastructure that is segmented into zones with virtual nodes that run network services; see Fig. 5.b. Services are realized by workflows that clients access through a gateway, which is also open to an attacker. The attacker aims to intrude on the infrastructure, compromise nodes, and disrupt workflows. To mitigate possible attacks, a defender continuously monitors the infrastructure by accessing and analyzing intrusion detection alerts and other statistics. It can change the network segmentation to respond to possible intrusions, e.g., it can migrate nodes between zones, change access controls, or shut down nodes. When deciding between these response actions, the defender balances two conflicting objectives: maximizing workflow utility and minimizing the cost of a potential intrusion.

We consider the task of learning an optimal segmentation control strategy against a dynamic attacker that adapts its strategy to circumvent the segmentation. We model this problem as a partially observed Markov game where the state defines the security status of each component in the infrastructure, the observation corresponds to the alerts generated by different monitoring systems in the infrastructure, the defender’s actions correspond to segmentation controls, and the attacker’s actions correspond to exploits and reconnaissance commands. For mathematical details about the game-theoretic model, see the full thesis.

Summary of Theoretical Results

The use cases described above are not intrinsically mathematical and can be addressed without theoretical analysis. However, a central theme of this thesis is that the key to achieving scalable and optimal incident response lies in exploiting structure. By structure, we refer both to intrinsic properties of theoretical models, such as optimal substructure and decomposability, and to structural characteristics of the IT system itself, such as network topology, dependencies between services, and resource constraints. Recognizing and leveraging these structures allows us to reduce computational complexity and design response strategies that are both theoretically optimal and practically deployable in operational systems.

All the mathematical models, proofs, and derivations underlying these theoretical results are presented in full detail in the thesis. The key theoretical contributions of the thesis can be summarized as follows: a) we prove structural properties of optimal response strategies, such as decomposability (see Thm. 3.2) and threshold structure (see Thms. 1.1, 2.1, 4.3, 4.5, 5.1); b) leveraging these structural results, we develop scalable approximation algorithms for computing response strategies (see Algs. 1.1–6.1); and c) we prove that these algorithms converge to response strategies with optimality guarantees (see Thms. 5.3, 5.4, 6.4).

Our dual focus on practical applicability and computational efficiency enables us to narrow the gap between theoretical and operational performance, as proven experimentally by the evaluation results presented in the next section.

Summary of Experimental Results

We address each use case described above through our general framework described earlier. Following this framework, we identify the parameters of each simulation through system identification based on data collected from the digital twin and we learn the strategies through simulation. The computational algorithms that we use are listed in Table 1 and the data that we use for system identification is available here. The environment for training response strategies and running simulations is a P100 GPU. The digital twins are deployed on a server with a 24-core Intel Xeon Gold 2.10 GHz CPU and 768 GB RAM.

| Model | Algorithm |

|---|---|

| Flow control POMDP | T-SPSA |

| Replication control MDP | PPO |

| Recovery control POMDP | Rollout |

| Flow control game | Self-play with T-SPSA |

| Segmentation game | Self-play with PPO |

| Replication control game | PPO |

Table 1: Reinforcement learning algorithms.

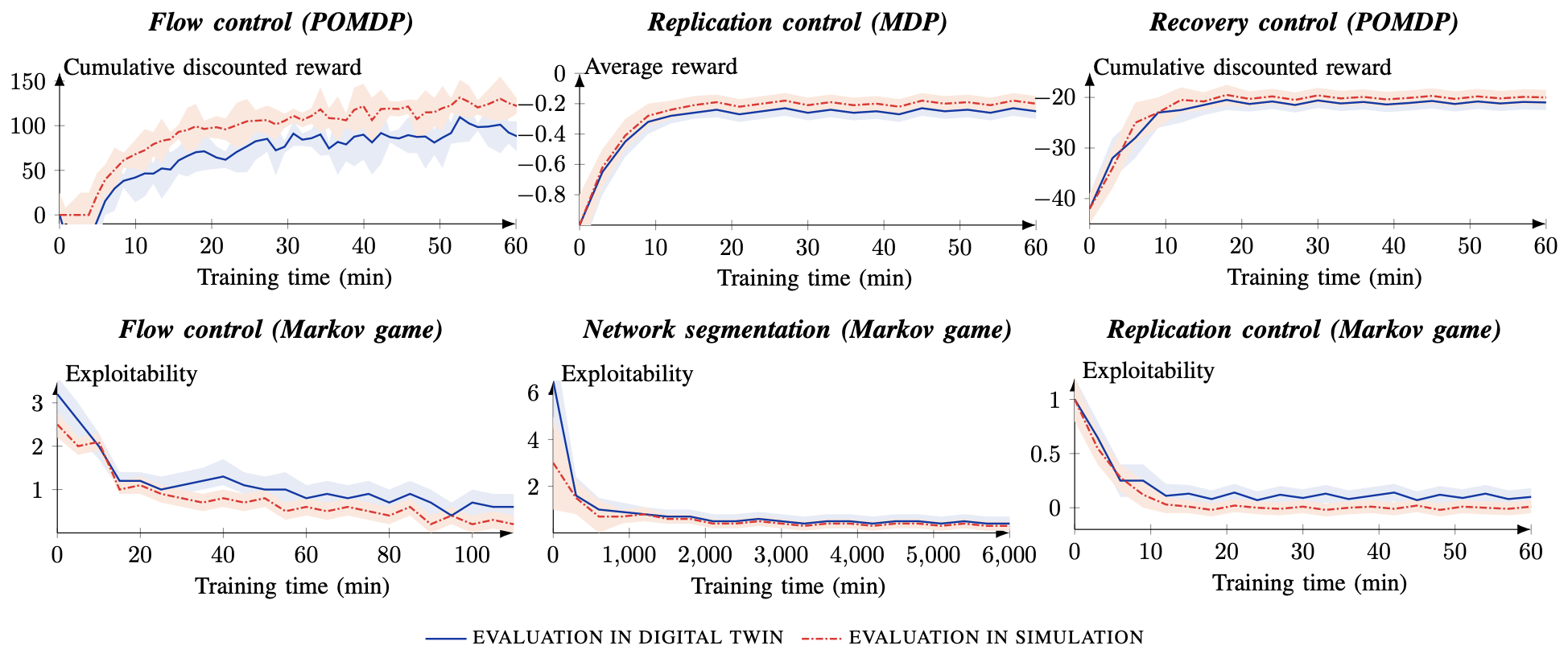

Evaluation metrics. We consider two evaluation metrics: the reward and the exploitability. The reward measures the performance of the learned strategy with respect to the defender’s objective in each use case and the exploitability measures the distance of the learned strategies from a Nash equilibrium. Specifically, as the exploitability approaches 0, the learned strategies become closer to a Nash equilibrium.

Evaluation Results

The evaluation results are summarized in Fig. 6. The red and blue curves represent the results from the simulator and the digital twin, respectively. An analysis of the graphs in Fig. 6 leads us to the following conclusions. The learning curves converge to constant mean values for all use cases and evaluation metrics. From this observation, we conclude that the learned response strategies have also converged.

Fig. 6: Convergence curves for the different use cases. The red curves relate to the performance in the simulations and the blue curves relate to the performance in the digital twins. Curves show the mean value from evaluations with 3 random seeds; shaded areas indicate standard deviations. The x-axes indicate the training time in simulation. The top row relates to Markov decision processes. The bottom row relates to game-theoretic models.

Although the learned response strategies, as expected, perform slightly better on the simulator than on the digital twin, we are encouraged by the fact that the curves of the digital twin are close to those of the simulator (cf. the blue and red curves). This small performance gap reflects inevitable discrepancies between the simulation model and the digital twin, such as differences in network latency, background processes, or unmodeled dynamics. However, it also indicates that the simulator provides a sufficiently accurate approximation for effective learning. Provided that the digital twin closely approximates the target system, the strategy is expected to maintain its performance once deployed on the target system.

Conclusion

The rising frequency of cyberattacks and their widespread impact on society necessitate automated incident response. Achieving such automation is one of the greatest challenges in cybersecurity. In this thesis, we have demonstrated optimal incident response in the most realistic attack scenarios considered to date. We achieved our results using a novel framework that combines a digital twin with system identification and simulation-based optimization. We argue that this framework provides a foundation for the next generation of response systems. The response strategies computed through our framework can be used in these systems to decide when an automated response should be triggered or when an operator should be alerted. They can also suggest, in real-time, which responses to execute. Unlike the simulation-based solutions proposed in prior research, our response strategies are experimentally validated and useful in practice: they can be integrated with existing response systems, they provide theoretical guarantees, and they are computationally efficient.

Thesis Material

The full thesis can be downloaded here and our framework is accessible here. The thesis was defended for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy on Thursday, the 5th December 2024, at 14:00 in F3, Lindstedtsvägen 26, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. Author: Kim Hammar. Supervisor: Professor Rolf Stadler, KTH. Opponent: Professor Tansu Alpcan, The University of Melbourne. Grading committee: Professor Emil Lupu, Imperial College London; Professor Alina Oprea, Northeastern University; and Professor Karl H. Johansson, KTH. Reviewer: Professor Henrik Sandberg, KTH.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Centre for Cyber Defence and Information Security (CDIS) at KTH, as well as the Swedish Research Council under contract 2024-06436. The author would like to thank his advisor, Prof. Rolf Stadler at KTH, for his continuous guidance, helpful suggestions, and criticism throughout his doctoral studies.